Week8 Identity, Algorithmic Identity, and Data

Discovering Sumpter’s Friend Categories

This week, I dived into Sumpter’s (2017) approach to categorizing his Facebook friends’ posts. He identified 13 categories, from family/partner and work to jokes/memes and activism. Then, using principal component analysis (PCA), he reduced them into two main dimensions: public vs personal and culture vs workplace. While these categories made sense, I felt some important aspects were missing. For instance, posts related to mental health or educational content weren’t represented, even though they’re quite common nowadays. Also, I realized how tricky it can be to force a single category onto a post that might overlap—what about a meme that’s also political commentary?

What’s Algorithmic Identity Anyway?

Cheney-Lippold’s (2017) idea of algorithmic identity was another eye-opener. It’s the dynamic identity constructed by algorithms based on our online behaviors—what we search for, who we follow, what we click on. These identities change constantly and often feel far removed from who we think we are. For example, Google has categorized me as an international student living in the UK (which is accurate). Based on this, I’ve been seeing ads for student accommodations! While it’s funny to think that Google “knows” I’m likely looking for housing, it also makes me wonder: how much of my digital identity is shaped by data I didn’t even realize I was providing? What’s unsettling is how these classifications happen without our input or consent, yet they affect everything from the ads we see to the content recommended to us. It’s both fascinating and unnerving to realize how much control algorithms have over shaping not only our online experiences but also how we might perceive ourselves.

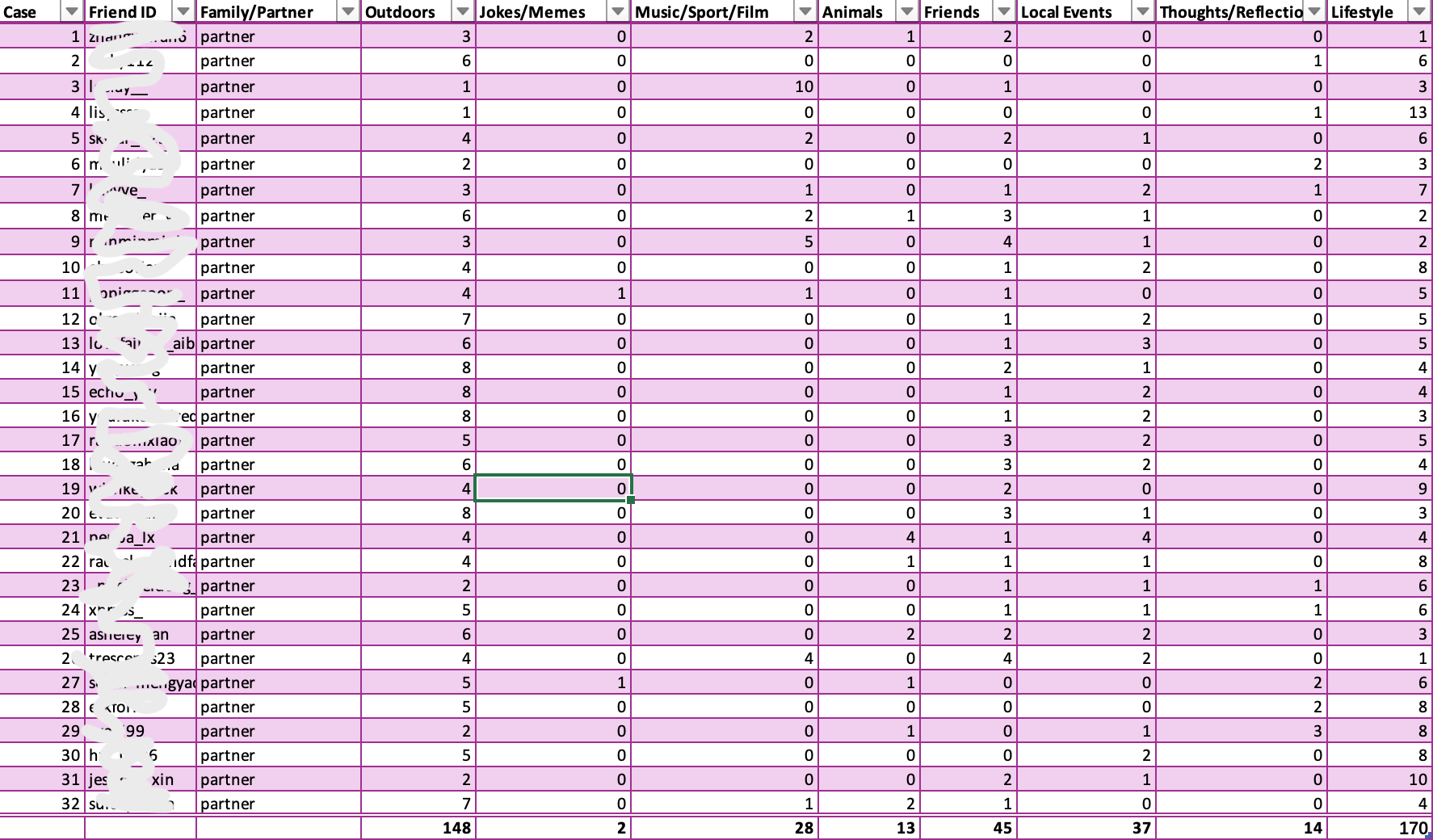

Building My Own Sumpter Model

As part of the workshop, I created my own version of Sumpter’s model using data from 32 of my Instagram friends. I categorized their most recent 15 posts and plotted some correlations. Unsurprisingly, “Lifestyle” posts were the most common—people love sharing snapshots of their daily lives. Interestingly, these posts were highly correlated with “Thoughts/Reflections”, suggesting that people who share about their lives often include introspective or personal commentary. On the other hand, categories like “Jokes/Memes” and “Animals” were much less frequent and didn’t overlap with other categories, making them feel more like niche interests.

The process was both fun and challenging. For one, reducing someone’s posts into numbers on a spreadsheet felt a bit weird, almost like I was oversimplifying them. And then there were those tricky posts that didn’t fit neatly into one category. For instance, is a selfie with a heartfelt caption a “Lifestyle” post or “Thoughts/Reflections”? These gray areas reminded me of how algorithms must struggle with similar decisions—and how their rigid classifications often fail to capture the complexity of real people.

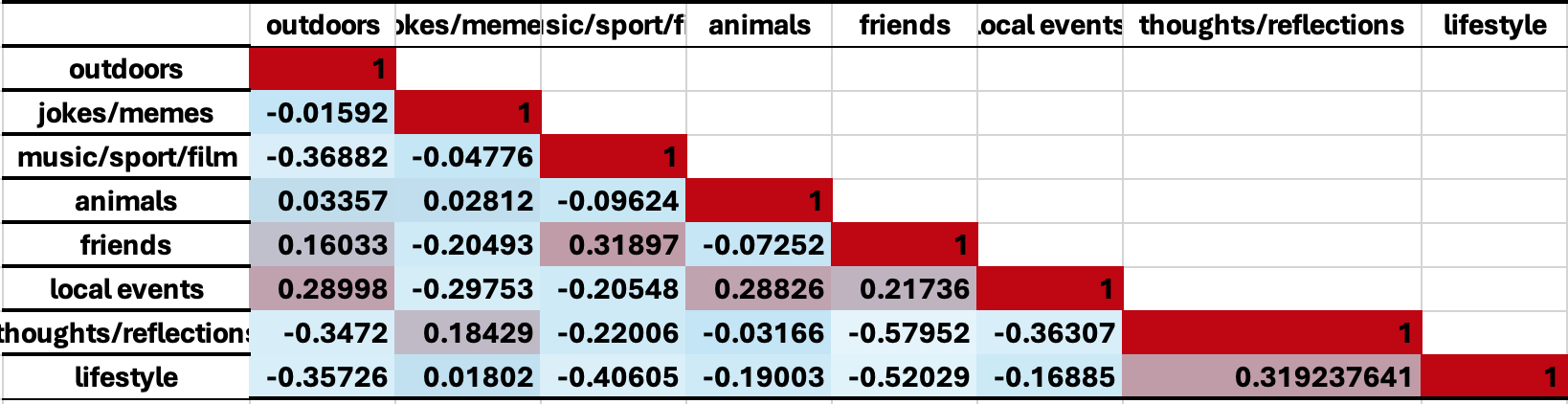

Interpreting the Heatmap

The heatmap I created provided valuable insights. Strong correlations, like that between “Lifestyle” and “Thoughts/Reflections”, highlight how users often tie personal and reflective content together. On the other hand, the negative correlation between “Thoughts/Reflections” and “Friends” suggests a possible divide—users focused on sharing their reflections might post less about their social interactions. These findings were fascinating but also highlighted the limits of fixed categories.

Being Seen Through an Algorithm’s Eyes

What stood out to me during this workshop was just how much algorithms simplify us. Google’s categorization of me as an international student was spot on, but that’s just one part of who I am. It doesn’t account for my creative interests, my love for cooking, or the fact that I’m probably more interested in Video Games than student housing! Cheney-Lippold’s idea of algorithmic identity highlights this gap—algorithms are based on patterns and probabilities, not the full depth of our personalities.

Where Do I Go From Here?

Looking back, this workshop helped me appreciate the complexity of algorithmic categorization but also left me thinking about how to improve. If I were to do this again, I’d expand the timeframe to include posts from different seasons—after all, people’s posting habits might change depending on the time of year. I’d also consider adding new categories like mental health or education to reflect the diversity of online content better. And maybe I’d ask my friends for their input—do they feel like their posts were accurately categorized? It’d be interesting to see how their self-perceptions align (or don’t) with my analysis.

Reference

Cheney-Lippold, J. 2017. Introduction. In: We Are Data : Algorithms and The Making of Our Digital Selves. New York: NYU Press, pp. 1-32

Sumpter, D. 2018. Chapter 3: The Principal Components of Friendship. In: Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to Fake News and Filter-Bubbles - The Algorithms That Control Our Lives. London: Bloomsbury