Personal Experience

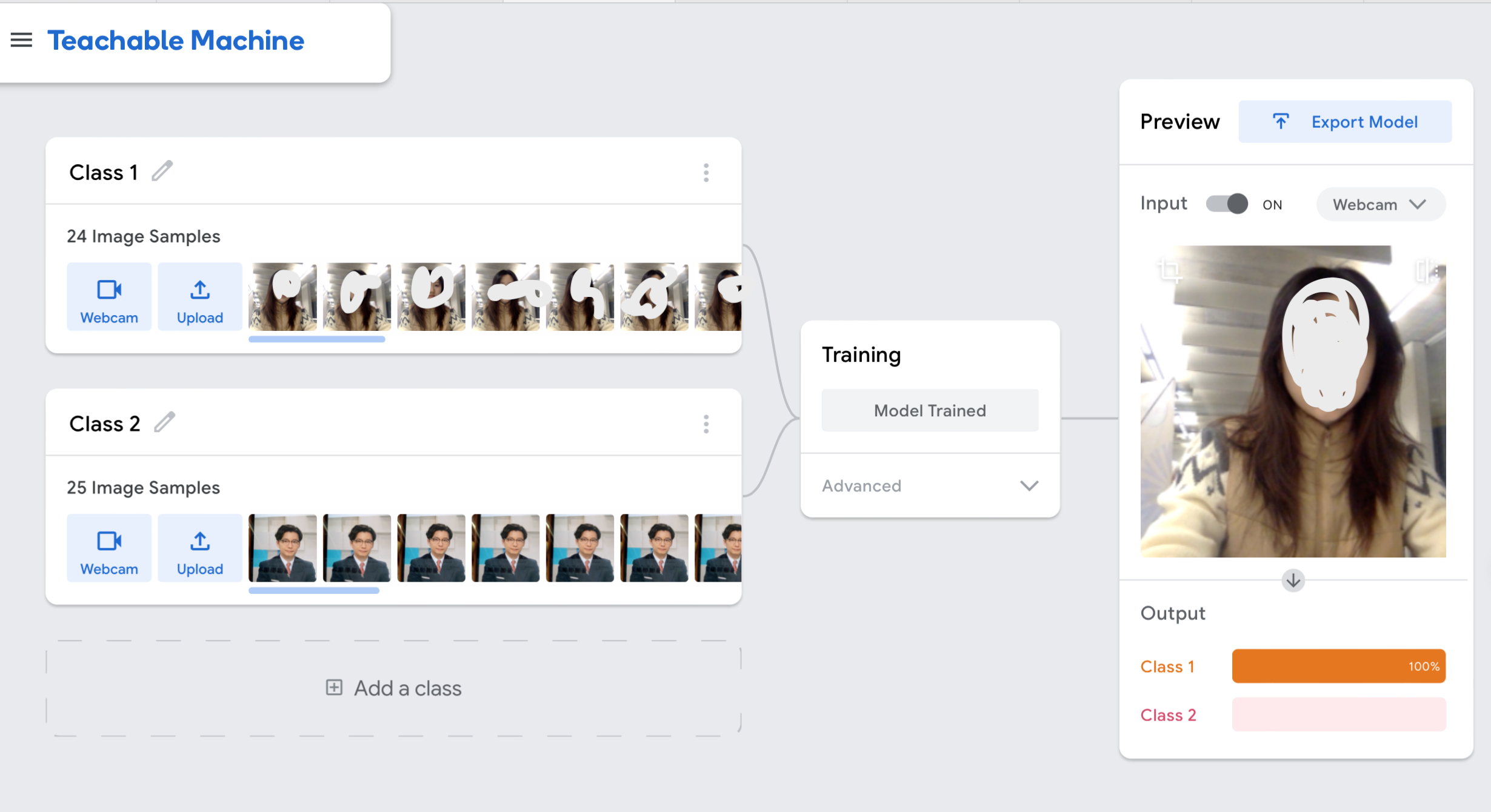

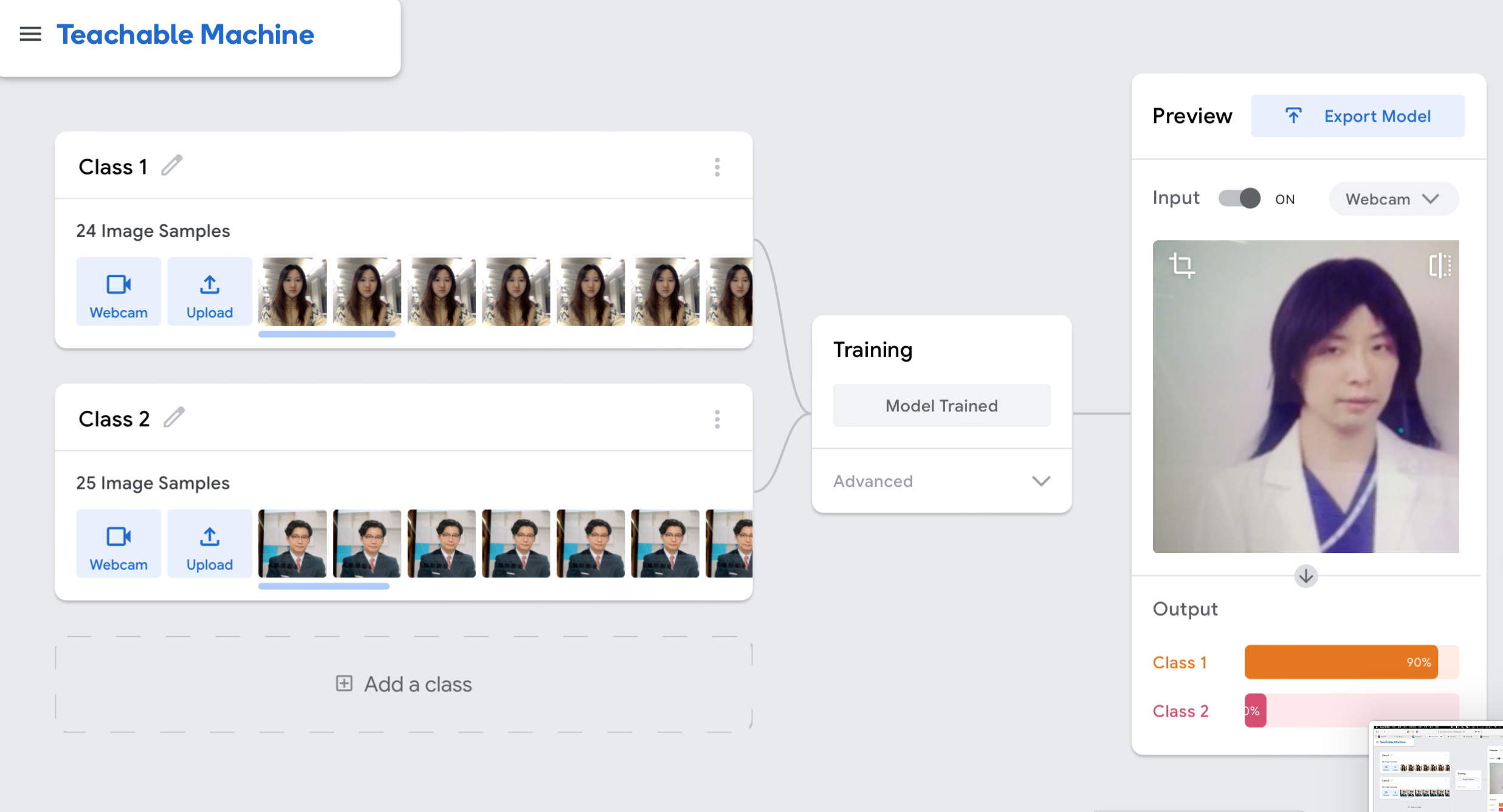

My exploration of machine learning started with the workshop 7 where I trained a model with Teachable Machine to categorize images. During the experiment, the database was divided into 2 classes: I upload my selfies as Class 1, and the photos of a Japanese male artist Hoshino Gen as Class 2. When I observed the model achieve 100% confidence in identifying my selfies, I was impressed by its capabilities. However, something unexpected happened: When the model confidently misclassified a picture of Hoshino Gen wearing a wig as "me," I burst out laughing. That moment stuck with me—it wasn’t just funny; it made me pause and wonder: how does the model actually see identity?

Clearly, it was relying on superficial features, like hair length or style, rather than understanding deeper context. The experiment made me think about how these models, no matter how advanced, are only as fair as the data they’re trained on. This realization echoed with the idea of Rana et al. (2022), models often inherit biases from their training datasets, including those related to gender and race. Similarly, Broussard (2023) argues that these algorithms don’t "think" in the way we do—they’re just mathematical systems amplifying patterns, including the problematic ones. De Vries and Schinkel (2019) add another layer to this, emphasizing that algorithms are shaped by the socio-technical norms embedded in the systems that create them. As I reflected on my experiment and the broader implications of utilizing machine learning to classify identities, these concepts seemed more important than ever.

Theoretical Connection

This experiment resonates with the findings of Scheuerman et al.'s (2021) paper, which highlights the historical biases embedded in automated facial analysis systems. According to the paper, such systems often reinforce essentialist and binary views of identity, rooted in colonial practices like physiognomy. These systems disproportionately rely on simplified visual traits, such as facial structure, skin tone, or hair length, to categorize individuals.

In my case, the model's reliance on hair length as a key feature led to misclassification, echoing the paper's argument that automated technologies often reduce the complexity of human identity to oversimplified visual markers. This practice highlights the broader challenges associated with machine learning technologies. Without diverse and representative training datasets, models are likely to reinforce biases and produce inaccurate or inequitable results. This has serious implications for critical applications, such as law enforcement, hiring, or public policy, where flawed classifications can perpetuate systemic inequalities. As Scheuerman et al. emphasize, there is a pressing need to address these biases to ensure that automated systems serve as tools for equity rather than exclusion.

Reference

- Broussard, M. 2023. More than a glitch: confronting race, gender, and ability bias in tech. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- De Vries, P. and Schinkel, W. 2019. Algorithmic anxiety: Masks and camouflage in artistic imaginaries of facial recognition algorithms. Big Data & Society. 6(1), p.2053951719851532.

- Rana, M.S., Nobi, M.N., Murali, B. and Sung, A.H. 2022. Deepfake Detection: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access. 10, pp.25494–25513.

- Scheuerman, M.K., Pape, M. and Hanna, A. 2021. Auto-essentialization: Gender in automated facial analysis as extended colonial project. Big Data & Society. 8(2), p.20539517211053712.